Dear Viven,

There are heaps of information in

guidebooks and on the internet about climbing Kilimanjaro, and I’m sure there’s

nothing I can say in this letter that you can’t find, confirm, counter or

disprove somewhere else. Nevertheless,

trekking up the mountain, which for most people is far away, is expensive and

universally challenging – and, in all likelihood you’ll only do it the once. Don’t leave your research to this letter

alone. But here are my two cents, even

if they are only worth two cents.

I climbed Kilimanjaro and reached the

summit on the six-day Machame route with my partner from 24 to 29 November

2013. We were clients of Zara Tours (http://www.zaratours.com).

The

Basics

It’s often said that climbing Kilimanjaro

is the most challenging thing you’ll ever do.

Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t. Many

people have a tough go, and more than half don’t make it to the summit (most because

of altitude sickness). Certainly there

are tougher, longer and less-catered climbs out there, but what makes

Kilimanjaro so difficult is the elevation.

It’s for that very same reason that so many (tens of thousands every

year) pay the big bucks and make the journey: you are literally on top of a

continent. And let there be no doubt: it

is beautiful, invigorating, fulfilling and, when you get to the top, quite

literally awesome.

There are exceptions to every rule, and

certainly ways around the orthodoxies of Kilimanjaro. If you don’t want to go with a company who

carries up your food, if you don’t want to go on a certified trail with a

certified guide, and if you want to spend a month near the summit doing a

scientific survey on your own personal hardiness and constitution, I’m sure

it’s possible. I’m also sure you’ll need

the money, time and force of will for dealing with Tanzanian bureaucracy. I’m not familiar with going around the usual

ways, and the rest of this letter will assume you are okay doing Kilimanjaro

like 98% of other climbers. In which

case, you’ll need to find a company, choose a route and time of year, pay a

price, and think a little about gear, altitude sickness medication, and even

tipping. Here goes.

Cost

& Company

Firstly, the longer your route, the more

expensive it will be. Thus, two of the

cheapest ways up are also the busiest: the Marangu and Machame routes. The Umbwe, meanwhile, can be cheaper because

of its short duration, but is by far the most difficult. Regardless, from my research and experience,

you should not be going outside the range of US$1400-2000 per person to climb

Kilimanjaro. If you are paying less,

expect some cut corners (poor gear, underpaid porters, inadequate food); if

more, expect not to notice the difference.

Park fees (including a mandatory emergency

rescue fee) are first and foremost what make the climb so expensive: they

amount to about $900 per person. Some

budget companies offer the climb for slightly more than $900, and they get you

up (if they can get you all the way to the top) by cutting expenses (say, for

tents that can withstand the rain) and by hoping you’ll make it worthwhile to

the underpaid, or unpaid, porters and guides with a big, guilt-induced

tip. These companies do exist and they can

work, but remember what you’re getting into.

On the other hand, some companies (like

Team Kilimanjaro or Duma Explorer) charge more money because, quite frankly,

they have a flashy website. Meanwhile,

outfits like the African Walking Company (which, admittedly, has a stellar

reputation) do not even sell their own services, but are arranged exclusively

through external, international sales teams, typically in the United States and

United Kingdom. This outsourcing is

bound to jack up the price, and it’s tough to source a Kilimanjaro climb

through an international agent that costs less than $2500.

There is little to no difference between

what these high-priced companies offer and what any mid-range option provides:

the food, equipment, guiding style, itinerary and amenities are practically

identical. This is not to mention some

companies which seem to be able to get away with charging upwards of $5000 per

person per climb. Don’t fall for it: do

a little homework, negotiate, and try to deal directly with the company with

whom you will hire for the climb. It may

also be a good idea to play the companies off each other to get the best rate.

Now, there are certain optional additions

that many companies offer which will add to the overall rate. You may request a private toilet in a tent,

which a porter carries for you at a typical extra rate of $50 per day (know

that the camp toilets are adequate, clean and usually close enough to your

sleeping tent). You may pay about $200

extra per person or more for oxygen tanks to be brought up (to be used only in

emergencies, and I understand if you use the oxygen before the summit, you will

not be allowed to continue upwards).

Some companies, such as Team Kilimanjaro, offer different rates for the

type of food you will receive. Expect to

save about $200 by eating only dehydrated food at meals, foregoing fresh fruit,

vegetables and meat – still, Team Kilimanjaro’s reduced rate (their ‘Lite

Series’ as opposed to the ‘Advantage Series’) remains above $2000 per person. Finally, if you do not have any of your own

gear, expect to pay upwards of $150 per person in rentals.

To put it in context, we paid $1550 per

person (originally $1650, but with a $100 discount earned by haggling) for a

six-day climb, meaning $275 per day, with Zara Tours. We climbed with a guide, assistant guide,

cook, waiter and six porters (three per person), and both reached the

summit. The guides were friendly, highly

competent, and spoke good English – to be frank, they were great. The tents and equipment were mostly fine,

though the duffle bags (packed with your personal belongings and given to a

porter to carry) weren’t waterproof, nor were the raincoats we rented. We were given two complimentary nights at

Zara Tours’ Springlands Hotel in Moshi; again fine, with helpful staff and a

swimming pool, but meals were not included.

Transportation to and from the airport was also included, but we only

requested an early-morning ride to the bus station – which didn’t show up and

nearly made us late for our bus.

Finally, while the packed lunches left a little to be desired and the

Zara-standard sausages got a little tiring, we generally received hot,

decent-quality, well-cooked meals using fresh meat, vegetables and fruit.

All in all, US$3100 ($1550 per person) got

us all we needed, and the service far outperformed other companies who charged

their clients a good deal more. Plus,

perhaps by mistake we got a private toilet, which we never requested or paid

for. It wasn’t bad at all.

Route

There are six main routes for getting up

Kilimanjaro: Lemosho, Machame, Marangu, the Northern Circuit, Rongai, and

Umbwe. There is quite a bit of

information about these routes out there, but here’s a summation. Lemosho: longer, scenic, less busy, good for

acclimatisation. Machame (the ‘Whiskey

Route’): scenic but busy, a little more difficult, and short but still great

for acclimitisation. Marangu (the

‘Coca-Cola Route’, named because porters used to haul up crates of Coke):

easier, busy, less scenic, less good for acclimatisation, and the only route

with accommodation in shared huts. The

Northern Circuit: newest, longest, least busy and thus most expensive route,

with good scenery and a good success rate.

Not all companies offer the Northern Circuit. Rongai: easier, longer, less busy, less

scenic but with typically better weather because it ascends from the

north. Umbwe: steepest, most direct and

most difficult, making it the shortest route (if you can do it without an extra

break) and usually only recommended to those with mountain climbing experience.

The Marangu, Rongai and Northern Circuit

routes all approach the summit from their own unique direction. Meanwhile, the Lemosho, Machame and Umbwe routes

(all Southern Circuit) offer two possibilities for the final ascent: the

standard, steep and zig-zagging wall-climb from Barafu, or the very difficult

Western Breach, for which you will need helmets, hands as well as feet to hold

onto the scree, and the light of day to ascend (all other routes start the

ascent at midnight, while the Western Breach begins at dawn). The vast majority of Machame and Lemosho

climbers aren’t even aware of the latter route, while many Umbwe climbers add

the Western Breach to their list of challenges.

Finally, there is an option to spend a

night in Kilimanjaro’s crater, just beneath the summit. This is available for any ascent on the

Southern Circuit or Western Breach (not to those on the Marangu, Northern

Circuit or Rongai routes). It gives

climbers the chance to tour the glaciers and reach the summit early without

needing to do a midnight climb. Keep in

mind that this option is very expensive, in large part to pay the porters. For them, this is the toughest job on the

mountain, and only the strongest may volunteer for the task.

My advice?

Find a route that best suits your needs and interests, and if you’re

anything like me, go Machame in the shoulder seasons, or Lemosho in the high

season.

Time

of Year

The main reason that people select a route

other than Machame or Marangu is to get away from the crowds, which are indeed

a big deal in the high season from June to October. But hikes from November to December and March

to May are typically not crowded on any route.

Though, I wouldn’t advise hiking Kilimanjaro at all in April and May,

unless you don’t care to actually see anything as you go up and down.

While the temperatures at Kilimanjaro’s

summit are always very cold, the levels of precipitation and cloudiness change

throughout the year. Generally,

Tanzania’s long dry season (also its tourist high season) from June through to

October offers a cloudless, rainless ascent to Uhuru Peak. The short rains from November to early

January provide a mix, while a second but short dry spell in February and early

March promises clearer views. In April

and May you can expect constant cloud cover and rain from top to bottom, with a

very good chance of a blizzard on the dark morning of your summit. Some climbers do go up at this time of year,

and the companies do run treks.

My advice?

Try to go at the start or end of the dry seasons to avoid the crowds, or

a less-traveled route in the middle of the high season. Or take a chance and go up in November and

December: it should rain in the afternoons, leaving the mornings (including

that of your summit) clear and warm.

Gear

If you are able, bring your own gear. Not only will it save you money, but you can

be confident in the quality (and waterproofness) of what you will wear. If you can’t (because, for example, you are

backpacking across Africa and carrying winter coats is a bit much), most

companies either have a store of rental gear or are partnered with somebody who

does. Arrive early enough to rent the

good equipment – and be prepared not to get everything you want in the high

season. Anticipate to pay for it. Alternatively, there are winter clothing

shops all over Moshi and Arusha, mostly selling used gear for an inflated

price. One shop I would recommend for

purchasing new gear in Arusha is Safari Care, in an outdoor shopping plaza next

to Shoprite: http://www.safaricare.com.

As for the gear itself, you will definitely

need the following:

- Very warm sleeping bags (company-issued are usually fine), rated to -20 °C at least

- Waterproof top and bottoms

- Long underwear, top and bottoms

- Fleece, top and bottoms, or other warm (not cotton) gear

- Down or other kind of winter jacket

- Outer waterproof shell jacket

- Good waterproof hiking boots, with high tops and solid ankle support

- Lightweight second pair of shoes, for camp wear when the hiking boots are wet

- Warm socks (avoid cotton, try for wool)

- Touque, brimmed hat, gloves, scarf, neckwarmer, etc.

- Headlamp for the midnight ascent to the summit

- Sunscreen

- Hiking poles (I never used them, but most people do)

- Optional: balaclava, skiing goggles, gaiters, chocolate bars, camera, book, Diamox

Altitude

Sickness & Diamox

Altitude sickness is a non-chronic illness

caused by exposure to a high-elevation, low-oxygen environment. In other words, when you go high up (usually

starting at 2400m) the air pressure decreases, there is less oxygen for you to

breathe, meaning negative effects on the body.

Altitude sickness can lead to more severe symptoms such as high altitude

pulmonary edema (HAPE) and high altitude cerebral edema (HACE), and both of these

can lead to death. So, don’t take it

lightly. Most people on Kilimanjaro who

suffer from actual sickness seem to get headaches, dizziness and an overall

physical weakness, and sometimes these symptoms are too harsh for them to make

it to the summit. The best treatment is

simply to descend.

I’ve heard it said that every second person

gets altitude sickness when climbing Kilimanjaro, starting at around 3000m (on

some routes, this is the first day). Of

all the people I met who didn’t make it to the summit because of altitude

sickness, about half took medication. In

other words: it seems to help, but it is no guarantee.

I suffered only from headaches, which were

severe from the very first night at Machame Camp (3000m) and occurred both at

rest and while hiking. I seemed to

acclimatise, get higher, get the headaches again, and then acclimatise once

more. At no point did I feel dizzy,

weak, nauseous or even short of breath.

Acetazolamide, or Diamox, is the altitude

sickness medication of choice, and many climbers take the drug or carry it with

them in case. The drug works by tricking

the body into believing its carbon dioxide levels are too high, thus inducing

heavier, faster breaths. It is advised

to take the drug before climbing, continuing dosage until descent, at one or

two pills (125-250mg) per day.

I can’t speak much for the overall

effectiveness of Diamox, or to the statistics for how it works, or about its

side effects. One climber, who didn’t

make it to the summit because of the altitude, refused Diamox because he was

warned that the side effects could be just as bad as the altitude sickness

itself. I didn’t take any prior to

departure up the mountain, and only popped three 125mg pills on the two days

before the summit (one on the evening of Day 3, and one each on the morning and

evening of Day 4) because the headaches were so fierce. I had to borrow the medication off another

climber who, luckily, could only get a prescription of 100. The medication seemed to alleviate the

intensity of the headaches, though not the headaches themselves, and perhaps

saved me from other symptoms; but it was not as effective as ibuprofen.

My advice?

Try Diamox for side effects before you go up, and if it’s alright, use

it.

Tipping

Tips are expected by your crew at the end

of any Kilimanjaro climb. Whatever

company you’re with will advise you to tip more than you really should. And worse, expect your guide to act

disappointed no matter how much you give.

The problem is that the tip-receiving is a practiced routine. Many companies will take you straight from

the finishing line at the bottom of the mountain to a restaurant to celebrate,

and there they’ll ask for the tip. You

won’t want to ruin the atmosphere, so when the guides and cooks and porters

sulk, you will feel the need to pay more.

Whatever your original tip, it will not be enough. When you start saying you don’t have the

money, they will often ask for other things: your hiking shoes, clothes, watch,

headlamp, etc. Don’t get worked up about

this: it’s all part of the trick to get more money. Chances are, so long as you aren’t truly

cheap, your tip will indeed be adequate and much appreciated – they just won’t

show it. To be blunt, it’s a part of the

training.

There are various standards of tipping out

there, but I feel that the most reliable one is to tip 10% of the overall cost

of the trip, and more if you were particularly impressed. You may tip in one large bunch (ensure, however,

that it is distributed properly and not pocketed) or disburse it

individually. If the latter, remember

the expected hierarchy of who gets more: guide, assistant guide, cook, waiter,

toilet porter, porter. You can tip in US

dollars or Tanzanian shillings.

For two people we tipped a total of 595,000

shillings, or US$371. This was about 12%

of the total cost of the climb. The tips

were divided as follows: 120,000 for the guide, 90,000 for the assistant guide,

60,000 for the cook, 50,000 for the toilet porter and waiter, and 45,000 for

each of the five other porters. And yes,

they were originally disappointed.

Like other companies, Zara Tours provides

its guides with sheets of paper to log all the tips per staff member, and these

documents must be copied, shown to all the staff, and kept on file by the

company.

My advice?

Tip 10% for a standard climb, more or less depending on your

satisfaction, and take the time to work out who gets what. And, defer the moment of tipping to the very end:

not when you get to the restaurant, not when you get to the gate, but right

before you part company.

Also, not all guides and staff behave like

this, but it is, sadly, the norm.

Links

Is this letter an inadequate guide with

insufferable errors and unforgivable blunders of judgment? Absolutely.

So go read some words which are wiser, better researched and more

thorough than mine. Specifically:

The Mount Kilimanjaro Guide. Exhaustive, well-written and fun, with no

bias to any specific company. Not sure

if you want to go? Get convinced.

Kessy Brothers. An operator with a good reputation; some

climbers we met were given free rental gear.

Climbing Kilimanjaro. A trekking provider with a great, detailed

website.

Zara Tours.

The largest operator with over a thousand staff. Middle-of-the-road, well-organised. A bit of an assembly-line feel, but decently

priced.

Team Kilimanjaro. The tour company with the best and most

informative website.

There are many others. It’s worth getting lost a little in

cyberspace to find them.

Does that do it? I hope so. I also wrote a letter to YouTube which includes a video montage of the climb, and some letters from the hike itself, dated on days 1, 3, 5 and 6, though

they might be a little more emotional than practical, flashy more than helpful. But then, that’s Kilimanjaro.

Happy scramble,

QM

|

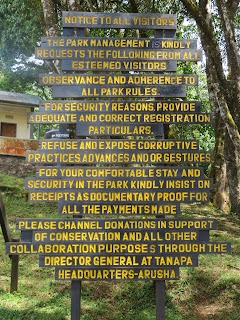

| Signs at the start of the Machame route |

|

| Signs at the start of the Machame route |

|

| Signs at the start of the Machame route |

|

| Signs at the start of the Machame route |

|

| Signs at the start of the Machame route |

|

| Looking up at the summit |

|

| View from Barafu |

|

| Sunrise on the Southern Circuit ascent |

|

| Towards the summit |

|

| Mawenzi Peak |

|

| Stella Point (5739m), about an hour from Uhuru Peak |